Haus Atlantis (2018)

16mm film, 9:38 min

Haus Atlantis conjures a glittering sci-fi fairy tale from one of the stranger corners of Nazi Germany’s cultural history. Through voice over, we learn of a people marooned in “a psychic disaster zone”. The Deep Sea Age has ended. In travelling to the bottom of the sea to plumb its mysteries, man has altered his consciousness. Now the oceans have retreated and the sub-aquatic research centre has long been abandoned to nature. Encrusted with coral, its secret architecture lies exposed to the elements.

It nonetheless seems to exert a power over the population. While mutant kelp engulfs houses and streets, a kind of seasickness has taken hold, spreading from the few to the many, all convinced that they once lived in Atlantis and dived next to Neptune and Noah. The afflicted withdraw to the sanatorium where they lie in darkened rooms and turn mystical, enraptured by visions of new species of starfish. The only visibly active members of this society are masked relic hunters who scour the dusty seabeds for the skeletons of dead mariners, as treasured as the bones of medieval saints.

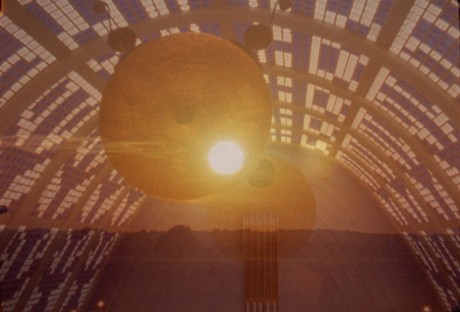

The visual accompaniment to this, progresses through old black and white photographs of bombed-out streets and footage of marshy countryside. Ruined buildings and boats are abandoned in a desert. Busts and statues of classical gods and heroes revolve against darkness, cast adrift from chronology or geographic context. The recurring image is the interior of a building as magnificent as an ocean liner. Its treasures include a blue mosaic barrel vault glass ceiling that curves above a vast hall and a spiral staircase bathed in watery green light. In a clue to the location’s present-day function 21st century businesspeople breakfast beneath chandeliers that hang like frozen jellyfish.

This is the film’s real world lynchpin, Haus Atlantis, an Expressionist building built in 1931 in Bremen, designed by the artist Bernard Hoetger and commissioned by businessman Ludwig Roselius in order to “restore the self esteem of the German people”.

Hoetger was inspired by Roselius’s belief that Germans originated in Atlantis and were thus the founders of civilisation. The building was conceived as an exhibition space for his collection of prehistoric artefacts and was meant to function as a cultural foundation combining Nordic mythology, pseudo-science and futuristic architecture that aimed to embody racial superiority.

Today, after being heavily damaged during WWII, Haus Atlantis remains in a ghostly state of incompletion and now forms part of a Radisson Hotel where it is being used and rented for conferences. While the monstrous sculpture of Odin that once graced its façade has gone, traces of its original purpose remain, including the glass-roofed Hall of Heaven (Himmelsaal) to which visitors would be lead on a spiritual journey from the bottom of the sea, where the ruins of Atlantis lay. It was essentially a temple to the superiority of the Germanic race, whose revival, according to Hoetger and Roselius, would be achieved through the power of its ancient past.

The notorious 1937 exhibition Degenerate Art, organised by the Nazi party to lampoon modern art, has cemented an art historical narrative that Nazism excluded the new ideas of expressionism and irrationality that Hoetger’s art embraced. Projects like Haus Atlantis however tell a different story, pointing to a time when Hoetger’s concerns overlapped with a national socialist interest in Nordic identity, soil and ancient forms.

Like its architectural touchstone, the film Haus Atlantis weaves together fragments of history and myth into a seductive fantasy. It circles a moment of flux, before events had been fixed in history books and ancient myths and occult ideas held prominent figures like Roselius and Hoetger in thrall. Mirroring their unconventional approach to the past, the film freely picks and mixes shades from bygone ages with visions of a yet to come civilisation, creating something new out of the old and the futuristic.